Trust, Hernán Díaz

Dimensional takes on one tale. The book’s first part feels slightly lackluster, but Díaz’s structural pivot halfway through dazzled. The different points of view remind us that there is no wrong interpretation.

Search, Michelle Huneven

The subject sounds dry as dust: the search for a new pastor. But Huneven’s delectation in the nitty gritty details of the search offer an optimistic way to savor the quotidian. She adds another layer with recipes.

The Lincoln Highway, Amor Towles (published 2021)

The title misleads; it isn’t a boring historical tract, but an engrossing caper with Huck Finn heroics and a satisfying plot twist to provide a sense of justice.

Vigil Harbor, Julia Glass

Bobbing between straight-up fiction and sci fi, a densely plotted novel that takes place in pandemic era Massachusetts examines a community through multiple characters and a dash of the supernatural.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, Gabrielle Zevin

I’m not a video gamer, but that discipline is the spine of this novel that follows a brilliant game designer through her personal life, which is far less clear than her coding. A modern version of an artist’s struggle and achievement.

Mecca, Susan Straight

A glimpse of So Cal people on the fringe of citizenship doing the work that keeps the dream alive, and the sacrifices and indignities suffered in daily life. A refreshing, less explored viewpoint.

Olga Dies Dreaming, Xóchitl González

Contemporary, successful Brooklynite siblings of Puerto Rican heritage confront varied scenarios, including a rebel absentee mother, a devastating hurricane, and the vicissitudes of political quid pro quos.

Still Life, Sarah Winman

Found families can sometimes be closer than blood relatives. Still Life stitches relationships between unlikely friends, across boundaries, during war time. Art transcends time and actual borders, and kind gestures merit astounding rewards.

Fellowship Point, Alice Elliott Dark

The main character is a strong-minded elderly woman writer, in itself a rarity, and her more traditional best friend. Questions the proprietorship of land, works of art, and one's self.

The Latecomer, Jean Hanff Korelitz

A bevy of unlikeable characters is partly redeemed by the titular character. Korelitz, who wrote The Plot, is highly skilled with storyline.

Sea of Tranquility, Emily St. John Mandel

St. John Mandel navigates the fine line between sci-fi and fiction, outlining a future of interplanetary commutes, where sounds can resonate between generations. She manages this with economy—no small feat.

NON-FICTION

Visual Thinking, Temple Grandin

The premise is scary—our country can’t make things anymore, in part because our education system has discouraged visual thinkers by setting Algebra 2 as a roadblock. Fascinating and kind of depressing, but Grandin puts forth ways to move forward.

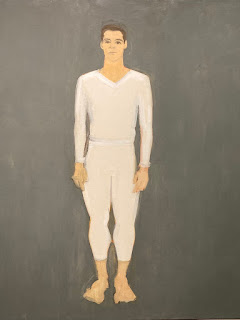

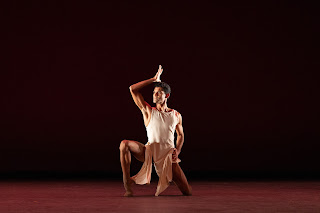

Serenade, Toni Bentley

Bentley explicates this essential ballet by Balanchine to Tchaikovsky’s score, while reminiscing on her own life at New York City Ballet. Every phrase of the dance is rich with meaning, made real through the artist/dancer.

The Impossible Art, Matthew Aucoin

This director/author elucidates the art of opera, a form I’ve found difficult to fully embrace. He also examines some of his own work and finds it wanting, which feels noble in this time of self-importance.