|

| Year. Photo: Carrie Schneider |

But Abraham has always done things a little differently, often with the larger community in mind. Post-show stage pleas have commonly focused on pleas to donate to Broadway Cares, which supports AIDS/HIV patient services. At the Joyce, he called out by names of all of A.I.M’s dancers, and all the artistic collaborators behind the scenes and sitting in the audience. His gratitude filled the house with genuine appreciation and affection.

He’s also full of choreographic surprises and experimentation, both dance-wise and structurally. His premiere, 2x4, from a broad perspective evoked early modern dance creators with its Big Art set and challenging music (I’m thinking Merce Cunningham). Devin B. Johnson’s immense artwork backdrop, in shades of magma, and the baritone sax score by Shelley Washington, played on stage by Guy Dellacave and Thomas Giles, who periodically stomped their feet and framed the quartet of dancers. Abraham’s unique style mixes catwalk sashays, ballet, gestures, and pedestrian behavior, as if he spliced video clips together from a random day. He’s in no danger of being pigeonholed, style-wise. This more formal work, with challenging music, contrasts strongly with recent works such as An Untitled Love for A.I.M, with its quasi-narrative sections set to D’Angelo, and major commissions for New York City Ballet.

|

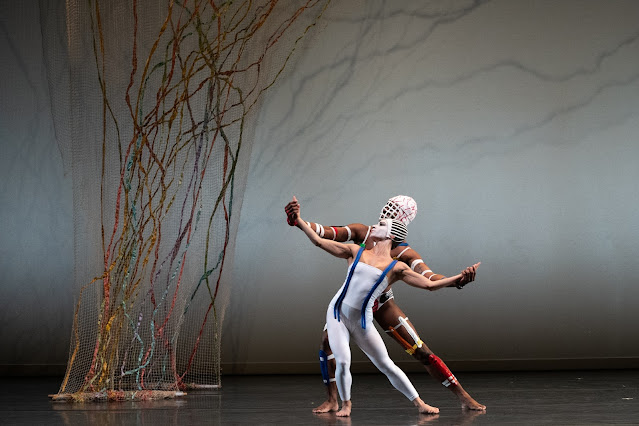

| Jamaal Bowman and Olivia Wang in Year. Photo: Carrie Schneider |

It was performed third and not last, which might be considered the “prime” slot on a bill. Andrea Miller’s Year (2024) took that honor, perhaps in part due to the installation of a largish set of three white walls surrounding the stage, and a craggy sun-like disc. The eight dancers wore Orly Anan Studio’s vivid unitards painted with surreal motifs—facial features and geometrical shapes. Fred Despierre’s percussion score contributed to the tribal feel. Miller trained in Gaga, and while that often percolates beneath the movement, it’s accented with a bit of voguing. The movement is sensuous, powerful, and expressive, and A.I.M’s skilled dancers wring out every drop, clustering and exploding, unspooling solos. Varied duets included one in which the woman skimmed above the stage, supported by her partner as he spun and leveraged her weight.

Paul Singh’s Just Your Two Wrists (2019) is an absorbing solo, here danced by Amari Frazier with an alternating ferocity and tenderness. (David Lang’s haunting music evokes Pam Tanowitz’s later usage in her memorable 2023 Song of Songs.) The program led off with Shell of a Shell of the Shell (2024), choreographed by Rena Butler to music by Darryl J. Hoffman. Butler is skilled with dramatic stagecraft—silhouetted dancers moving elastically, six pinlit performers isolated yet proximate, shows of extreme emotion in spasmodic or reactive moves. Yet it all felt a bit familiar, other than Hogan McLaughlin’s coarse ecru pantaloon and halter top costumes.

Abraham’s 2x4 almost felt like the answer to the question: which one of these is not like the other? His readiness to take risks by using squawking and stamping sax players, and reset his movement vocabulary for this piece, show why he continues to be lauded and watched carefully. But showcasing three contemporaries, and acknowledging all of his collaborators, reveal an uncommon generosity that runs through his body of work.

%20Lee%20Duveneck,%20Christina%20Lynch%20Markham,%20Eran%20Bugge,%20Kristin%20Draucker_photo%20by%20Ron%20Thiele.jpg)