|

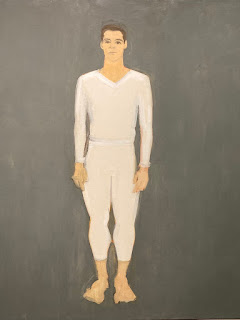

| John Harnage in Solitaire. Photo: Whitney Browne |

"Taylor—A New Era"

These simple, clear words headlined the cover of Paul Taylor Dance Company’s Playbill for its 2022 fall run at the Koch Theater. Since the later years of the founding choreographer’s life (he died in 2018), under the leadership of Artistic Director Michael Novak, the organization has been trying out different strategies for moving forward without new work by Taylor. After a confusing tango with the Paul Taylor American Modern Dance umbrella (begun by Taylor himself) under which a varied slate of American choreographers were commissioned to create new works on the Taylor dancers, things seem to have reverted back to the old PTDC moniker, or simply Taylor.

Branding aside, the programming concept has certainly evolved. The Orchestra of St. Luke’s continues to be the house band, but this time, it performed musical selections with no dance on a handful of programs. While I enjoyed hearing excerpts of Philip Glass’ The Hours by the orchestra, I couldn’t help feeling that it was a bit of a wasted opportunity to showcase the talented dancers who were backstage. Nonetheless, it highlighted the importance of live music to the company.

On a bright note, Lauren Lovette’s premiere of Solitaire is further proof of her creative talent, and that naming her resident choreographer for five years was a wise choice by Novak, if somewhat of a gamble. Substantial on many levels, Solitaire featured the crisp, elegant John Harnage in the sort of poet-on-a-journey role not unfamiliar to fans of Taylor’s oeuvre. It is set to music by Swiss composer Ernest Bloch, with dramatic string sections and a sense of gravitas and impetus. Santo Loquasto designed costumes and the set, which included an ominous diamond-shaped element that loomed like a guillotine over a serene mountainscape, descending and rising.

But what pops is Lovette’s facility with making modern phrases that flow organically, but which challenge the skilled company’s technical chops seemingly beyond what most of the repertory has until now. That’s not to say that Taylor’s vocabulary is not challenging, but Lovette’s accomplished ballet career heretofore has likely seeped into her movement—in the best way. It’s not ballet, but there’s an integrity and underlying structure that comes across. She has also found a way to convey an unspecific narrative that feels like a rich story waiting to be written. Solitaire was sandwiched between Taylor’s joyful, bittersweet Company B and Syzygy, a study in freneticism done in a completely different vocabulary, forming a satisfying slate with breadth.

Speaking of which, the season included Kurt Jooss’ The Green Table, another example of the expansion of the troupe’s artistic horizons. (It had been remounting classics of American modern dance in pre-Covid seasons, but not by international artists.) This classic 1932 work about the senselessness of war, and how it is wrought by those far from the battleground, remains timeless and gut-wrenching. It makes sense for Taylor to take on this legendary dance, with its muscular phrasing and trenchant messaging. A bonus was seeing Shawn Lesniak in the role of Death (once danced by Jooss himself), carving sharp swaths, and forming perfect, machined angles with his long limbs. In other dances, without the lavish mask, makeup and headdress, I could see Lesniak’s gifts anew, and look forward to seeing him in more and more big roles.

Alex Katz—Gathering, Guggenheim Museum

Branding aside, the programming concept has certainly evolved. The Orchestra of St. Luke’s continues to be the house band, but this time, it performed musical selections with no dance on a handful of programs. While I enjoyed hearing excerpts of Philip Glass’ The Hours by the orchestra, I couldn’t help feeling that it was a bit of a wasted opportunity to showcase the talented dancers who were backstage. Nonetheless, it highlighted the importance of live music to the company.

On a bright note, Lauren Lovette’s premiere of Solitaire is further proof of her creative talent, and that naming her resident choreographer for five years was a wise choice by Novak, if somewhat of a gamble. Substantial on many levels, Solitaire featured the crisp, elegant John Harnage in the sort of poet-on-a-journey role not unfamiliar to fans of Taylor’s oeuvre. It is set to music by Swiss composer Ernest Bloch, with dramatic string sections and a sense of gravitas and impetus. Santo Loquasto designed costumes and the set, which included an ominous diamond-shaped element that loomed like a guillotine over a serene mountainscape, descending and rising.

But what pops is Lovette’s facility with making modern phrases that flow organically, but which challenge the skilled company’s technical chops seemingly beyond what most of the repertory has until now. That’s not to say that Taylor’s vocabulary is not challenging, but Lovette’s accomplished ballet career heretofore has likely seeped into her movement—in the best way. It’s not ballet, but there’s an integrity and underlying structure that comes across. She has also found a way to convey an unspecific narrative that feels like a rich story waiting to be written. Solitaire was sandwiched between Taylor’s joyful, bittersweet Company B and Syzygy, a study in freneticism done in a completely different vocabulary, forming a satisfying slate with breadth.

|

| Shawn Lesniak and Jada Pearman in The Green Table. Photo: Ron Thiele |

Speaking of which, the season included Kurt Jooss’ The Green Table, another example of the expansion of the troupe’s artistic horizons. (It had been remounting classics of American modern dance in pre-Covid seasons, but not by international artists.) This classic 1932 work about the senselessness of war, and how it is wrought by those far from the battleground, remains timeless and gut-wrenching. It makes sense for Taylor to take on this legendary dance, with its muscular phrasing and trenchant messaging. A bonus was seeing Shawn Lesniak in the role of Death (once danced by Jooss himself), carving sharp swaths, and forming perfect, machined angles with his long limbs. In other dances, without the lavish mask, makeup and headdress, I could see Lesniak’s gifts anew, and look forward to seeing him in more and more big roles.

As much as (most of) the previous generation of dancers is missed, it is a pleasure to become acquainted with the new one. The dancer who seems to now be the most cast, at least in prominent roles, is Madelyn Ho, who was in everything I saw over three programs. She counters her small size, which might be less visible to the uppermost seats, with an extra dash of verve and joy. She dances with delicacy and articulation, plus ferocity and athleticism. Arden Court showed off many of the newer men—the explosive Alex Clayton, a soaring Devon Louis, and the sheer joy of Austin Kelly.

|

| Maria Ambrose, John Harnage, Shawn Lesniak, Jada Pearman, Kristin Draucker in Polaris. Photo by Ani Collier |

The season coincided with Gathering, a Guggenheim retrospective of Alex Katz’s work, who designed many works for Taylor. Two outstanding Taylor/Katz collabs from the 1970s—Polaris and Sunset—were performed on the season finale program. Both display Taylor’s varied genius. Polaris, in which the same movement is performed by two different casts, with varied music, lighting and mood, rendering two completely unique dances; and Sunset, with its lush, romantic score by Elgar (plus loons), its old world approach to flirting and courting, and the contrasting depiction of an unrequited bond between two soldiers.

Katz’s show at the Guggenheim includes a portrait of Taylor, as well as a painting of the company performing. It’s hard to say what makes Katz’s work feel so quintessentially American—the distinct light, the flat expanses, the reductive line and composition, or all of the above? The exhibition includes some of his more intrepid experiments, such as painted aluminum cutouts (he created a bunch of dogs like this for Taylor’s Diggity) and repeated images of his wife Ada within one picture. The coincidence of his retrospective with a featured spot in the Taylor season underscored the artist’s continual output in the last half century.

Transverse Orientation, BAM

|

| Paul Taylor, by Alex Katz |

Katz’s show at the Guggenheim includes a portrait of Taylor, as well as a painting of the company performing. It’s hard to say what makes Katz’s work feel so quintessentially American—the distinct light, the flat expanses, the reductive line and composition, or all of the above? The exhibition includes some of his more intrepid experiments, such as painted aluminum cutouts (he created a bunch of dogs like this for Taylor’s Diggity) and repeated images of his wife Ada within one picture. The coincidence of his retrospective with a featured spot in the Taylor season underscored the artist’s continual output in the last half century.

Transverse Orientation, BAM

BAM presented Transverse Orientation by Dmitris Pappaionnou, whose Great Tamer had been shown a few years ago. The big imprimatur for Pappaionnou was that he was the first choreographer to be commissioned by Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch after her sudden death, as well as creating the opening ceremony for the 2004 Athens Olympics. So many artists have been influenced by Bausch, but most have been careful to avoid direct quotes. But Pappaionnou took the plunge with Transverse, inserting vignettes evocative of Bausch—a woman transformed into a fountain, and a giant wall built of foam blocks which toppled forward. Somehow it felt okay, as if enough time has passed, and because he has collaborated with TWPB. Tanztheater lives, and this iteration felt like a proper homage to Bausch and another phase in the form's continuum.

I can’t say enough about the main protagonist in Transverse, a life-sized bull puppet designed by Nectarios Dionysatos. The dancers skillfully manipulated the bull’s head so as to act as how I imagine a bull would, although it was more Ferdinand than raging. Others moved his hooves and tail, also amazingly expressive. The bull served as a sort of id to man’s ego, represented in oft-naked performers.

I can’t say enough about the main protagonist in Transverse, a life-sized bull puppet designed by Nectarios Dionysatos. The dancers skillfully manipulated the bull’s head so as to act as how I imagine a bull would, although it was more Ferdinand than raging. Others moved his hooves and tail, also amazingly expressive. The bull served as a sort of id to man’s ego, represented in oft-naked performers.

The piece is constructed of many scenes, most short and some quite long, that evoke a range of sensations—humor, awe, absurdity, pathos, and so on. Magically, images crystallize from thin air, as a madonna-like woman cradled in a sheaf, bearing a dripping object that turns out to be a baby. She is subsumed into the stage floor, which is torn up to reveal a lagoon. A man swabs at the pool futilely with an old mop. I thought of melting permafrost and our inability to take action in the face of an existential crisis. And then walking to the subway past the Opera House's load-in doors, where the lagoon was draining onto Ashland Place, of the magic of theater to deliver such messages.

No comments:

Post a Comment