A recent Sunday spent there says no!, at least when the weather cooperates, which it did, splendidly. Show times were staggered so that it was possible to take in Dichotomous Being: An Evening of Taylor Stanley at noon, and Black Grace at 2pm. Stanley and company occupied the outdoor Leir Stage, while the New Zealand troupe performed in the Ted Shawn Theatre. Each show was preceded by a short talk given by a scholar, and there was just enough time between shows to see the exhibition in Blake’s Barn (historic photos juxtaposed with new versions by photographer Christopher Duggan) or visit the amazing archive, wander, chat, partake of a snack or beverage, and stretch the old legs. Literally every moment can be infused with some kind of dance experience.

The two performances featured vastly different artists. Stanley is a pre-eminent principal with New York City Ballet, accomplished on every level in ballet, but also a revelation in contemporary choreography. Dance makers such as Kyle Abraham (an artistic advisor on this Pillow run) and Andrea Miller (who contributed Mango) have both created roles on Stanley for NYCB which utilize his boundless expressive gifts to the extent where I can’t imagine them danced by others. (They will eventually, of course, but for now, he reprises at least his iconic solo in Abraham’s The Runaway.)

The repertory Stanley (who goes by they/them) chose reflects the artist’s breadth. Classical ballet led off the program—an excerpt from Balanchine’s Square Dance (1957), which they performed with ease but tremendous focus, evident even while they ascended the side stair leading to the stage. Miller’s Mango (2021) was next, quite different when pulled out of the longer work, Sky to Hold—and easier to see the dance and dancers without the elaborate sets and costumes of the Koch Theater production. Ashton Edwards, who wore pointe shoes while the other three had on soft slippers, was lifted and partnered more than the others, but there was a lack of traditional gender dynamics that ballet so stubbornly perpetuates. Stanley performed Talley Beatty’s Mourner’s Bench (1947), an austere work in which the bench becomes not just a place to sit, but to revel, pray, and suspend from as one might from a ship’s prow.

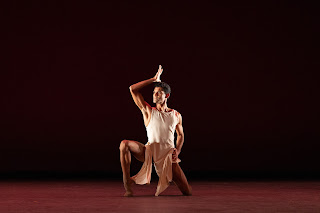

Jodi Melnick's world premiere of These Five (2022), is set to sonic experiments by James Lo including, confusingly, birdsong; I thought the nearby birds were just really loud. The performers placed tree branches center stage (which were quickly moved upstage), augmenting the theme of nature. Melnick’s post-modern style is essentially drained of emotion and interaction, but is full of unpredictable invention. The finale and another world premiere, Redness (2022) by Shamel Pitts, featured Stanley solo once more, moving with animalistic stealth, skipping, gesturing in catharsis, before ending in a catwalk strut for curtain calls. Stanley finally broke their transcendent stage demeanor to stretch high to the sun before collapsing in an expression of relief and gratitude after the run’s last performance.

|

| Black Grace in O Le Olaga. Photo: Danica Paulos. |

Black Grace, founded by Neil Ieremia who is of Maori and New Zealand descent, combines the dance and storytelling traditions of the South Pacific with contemporary elements. Perhaps one of the most recognizable sub-styles included is the “haka,” the ceremonial Samoan dance featuring stamping, chanting, and hand and facial gestures, made popular by New Zealand’s rugby team in its pre-scrum ritual. The troupe’s 14 members include not only dancers, but traditional artists and musicians. Minoi (1999), based on the haka, is a brief work for six men, full of chanting, super-quick arm moves, body slapping, stamping, done in a tightly packed formation.

Fatu (2022) showed how Ieremia has combined contemporary movement with traditional. Demi-Jo Manalo, a compact, powerful woman, danced to live percussion with James Wasmer and Rodney Tyrell, each wearing a different colored sash. The energetic choreography was full of floor work, flying leaps, sometimes into another dancer’s arms, and precise poses. The final work, O Le Olaga (2022) featured Aisea Latu as a kind of host, preceding many company members who enter a few at a time, establishing their own phrases. They eventually split into the traditionalists and the modernists. The presence of Western garb perhaps represented the dilution of indigenous culture, but it was countered by traditional rituals, movements, and vocalizations.

The main accompaniment was Vivaldi’s Gloria—a juxtaposition of Western classical with Pacific classical. Some of the space-eating modern dance passages done to Vivaldi brought to mind modern icons such as Mark Morris and Paul Taylor. Is it because, to my mind, they have used early and classical western music repeatedly, with joyful and explosive leaping and spinning? That’s not to cast shade on Ieremia’s creative output, which is unique and avoids a travelogue approach. He has managed to retain authentic Maori traditions while forging a name in contemporary concert dance. It’s a credit to his ability to find performers who can admirably straddle trad and mod.

To top off the whole Pillow experience, just after each show ended, I received an email from the Pillow which included a link to the artist's talks done earlier in the run. Kudos to the Pillow for providing a comprehensive, contextualized dance experience like no other.