|

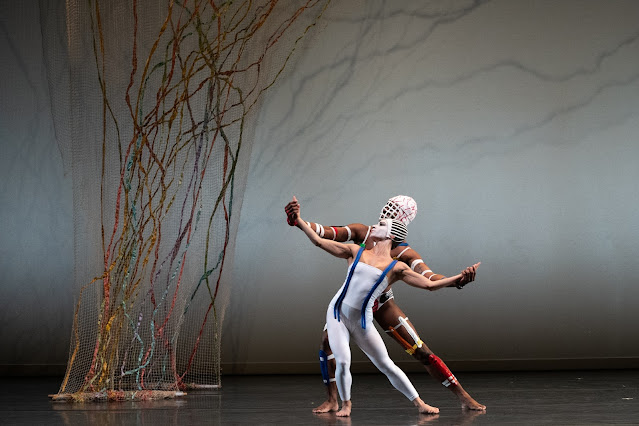

| Lisa Borres & Devon Louis in Fibers. Photo: Ron Thiele |

That’s the takeaway from seeing Paul Taylor Dance Company’s program on June 14 at the Joyce. Artistic Director Michael Novak has smartly programmed some of Taylor’s early dances, such as Fibers and Images and Reflections, in which the choreographer experimented and sketched out seminal shapes and ideas to form an essential vocabulary from which he drew to create paragraphs. These precede later major pieces, also performed—Profiles, Aureole—which assembled these motifs in dazzling phrases to make an incomparable body of modern dance.

The program differed greatly in feeling from the company’s recent spring stint at City Center’s Spring Dance Festival, which featured mostly romantic or classical dances—soothing in a time of chaos, but not wholly representative of the choreographer's breadth. (Taylor, who died in 2018, often included one crunchier dance, either a psychological study or social commentary, in an evening of three pieces.) The early works seen at the Joyce are mostly shorter, or excerpted, eschewing the three-dance-per-evening formula (be it tried and true). The four Taylor dances bookended a premiere by Michelle Manzanales, a reminder that while rooted in Taylor’s oeuvre—ever more distant with each passing year—the company must continue to look ahead.

Taylor collaborated often with designers, including well-known artists. Rouben Ter-Arutunian created the fantastic contraptions and garments for Fibers (1961). The mens’ are the focus—colored and white straps encircling limbs and torso, hockey goalie-type face masks concealing the face, thus redirecting attention to the whole body. The women’s faces are painted white, to match the white unitards with blue details. While the piece forefronts the movement’s drama, enhanced by the costumes, it drops key shapes and moves that emerge in Profiles and Aureole.

|

| John Harnage in Images and Reflections. Photo: Ron Thiele |

Robert Rauschenberg contributed costume designs for Images and Reflections (1958). The first two evoke underwater creatures, especially in the dark lighting scheme—John Harnage, whose lucidity has emerged even further alongside confidence and strength—sports a long white mane on his unitard; Kristen Draucker wore a skirt of fin-like pink panels. Devon Louis (busy guy, in all but one dance on the slate) wore silver panné head to toe. The dancers made clear shapes, moving from pose to pose, or between short phrases, which were detached from the Morton Feldman score. Lyrical, arcing arms could be spotted in Aureole; explosive jumps in Profiles, to follow.

|

| Madelyn Ho, John Harnage, Alex Clayton, Eran Bugge in Profiles. Photo: Ron Thiele |

Profiles (1979) is a brief but daring study in extreme partnering. Beginning in his flat, Greek vase style—in profile—it evolves as the two pairs do what looks to be impossible. A woman, assisted by her partner, leaps onto his shoulder like a cat, or bounces high off of his chest. The two pairs form a lattice, the women balancing on the mens’ thighs. Profiles shows the potential of partnering beyond a pretty lift, and the steely strength required not just of the men, but the women.

In Aureole (1962), Taylor seemed to have taken all these striking shapes and strung them together with fluent connecting phrases, set to melodic Handel. Gone are the arty costumes, replaced with classical, crisp white leotards and dresses. Taylor’s new classicism took root in Aureole. However, it wasn’t a total break from the conceptual experiments into which Taylor had delved, nor the high drama of his days as a dancer with Martha Graham. He would also pursue these threads in his widely varying body of work, which still defies easy definition.

|

| Hope Is the Thing with Feathers. Photo: Ron Thiele |

Manzanales choreographed a premiere, Hope Is the Thing with Feathers, a suite set to a range of songs about birds. It’s fun, jaunty, and the dancers seem to be enjoying themselves. It is no cakewalk to be juxtaposed with prime examples of Paul Taylor’s choreography, but she acknowledged a debt to his influence by inserting Taylor quotes now and then—the arced, flowing arms, certain shapes and leaps. Then again, he created so many dances, and so many kinds of dances, that his influence can be found if you simply look for it in much of the work created in his wake. Even just walking down the street.

Concurrent with the PTDC Joyce run, Gladstone Gallery ran two shows of early work by Rauschenberg (and one at Mnuchin, which I missed). As is often the case in New York these days, the shows were of museum quality. Many of the works are made of cardboard and found objects—tires, paper bags, bikes, furniture, muslin. While watching the early Taylor work, I couldn’t help but think how, in the right hands, the simplest materials or human shapes ordered a certain way can become enduring art. How providential to catch displays by these collaborators at the same time.